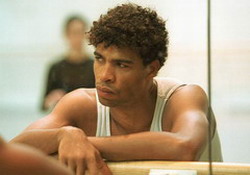

Carlos Acosta: a ballet superstar

- Submitted by: admin

- Arts and Culture

- Dance

- 09 / 30 / 2007

When the great Cuban dancer Carlos Acosta left Havana to join English National Ballet in 1991, there were two fears in his homeland: that he would suffer ideological subversion, and that his Cuban identity would shrivel in the grip of western decadence.

Sitting opposite the 34-year-old as he discusses his new autobiography, if he were chomping a cigar and sipping a Cuba libre, he couldnt be more the proud habanero. Testosterone courses; preconceptions about ballets fey charms crumble.

His dancing, famed for its superhero leaps and dynamo turns, used to be called "feral", and there is still something wild about him as he yawns and stretches on the sofa to the clickety-click of his right patella. "My knee and toes hurt." He grins. "You learn to live with the pain." When we part, he will seek out a massage; he has come a long way from the Cuban religion of Santeria, in the name of which a witch doctor once anointed a dance injury with the boiled-up skin of a sacrificial ram. "Never again," he laughs. "Though it might have worked."

Acostas book is called No Way Home, and for much of his career, that is how he has felt: rootless, isolated, a little lost. "Home was what I was longing for," he says in his still thick Hispanic accent, "to have my family."

At 16, his father told him to forget about them and make his way in the world, a cruelty he thought would liberate the boy to concentrate on his career. It was not what Junior, as he was known, wanted to hear. He was alone and often friendless in his "improved" life in the hyper-competitive world of big-league ballet in England and America (he joined ENB in 1991, Houston Ballet in 1993, the Royal Ballet in 1998), where every new hiring is a potential usurper of leading roles.

"At times, I have hated the desolate life ballet gave me," he says. While he was away, the picture at home grew ever bleaker: the collapse of the USSR left Cubas economy strangled, his mothers health was frail, his sister Berta suffered from suicidal schizophrenia. "I wanted to help, but I couldnt be there, because I had to be dancing, dancing, dancing all the time." After failed knee operations, he returned to Cuba in 1992 and didnt dance for a year, nearly giving up. "I told my girlfriend, 'Why the pain, why waking up so early in the morning to hammer your body? I was so sick of it."

But dance has been his exit strategy. For him, its not a passion he has chosen to pursue or a vocation he has honoured. Its a way of not being poor, more about survival than art. "My family were relying on me, too. The lack of choice is what gives my dancing its drive. Dance is all I have. I have to be good."

When he walks though the room at the Royal Opera House, shoulders thrust back, hot from a days classes, he looks too young to have lived the life he describes.

Born in the Havana suburb of Los Pinos, Acosta was a mildly delinquent son of a poor family, chewing sticking plaster for gum, stealing mangos to fill his belly, playing truant, watching his father go to prison after a traffic accident. "But I was happy. I didnt have big dreams. I was content with friends, the forests and the pools. I never had a sense of need or struggle."

The youngest of 11 children, he was sent to ballet school by his father, the grandson of a slave, to keep him off the streets, where he was a break-dancing champion, spinning on his head for gang approval. At first, he was the reluctant prodigy, nurtured and pushed by a series of teachers who forgave his absenteeism and cheek (he was nicknamed Junior el Disastre) for the sake of his promise.

In prerevolutionary times, his father had crept into a cinema and become entranced by ballet in a silent movie. He was ejected for being black, and, though the relationship has been volatile - and, at times, brutal - the success of the son has been a way of avenging that insult.

In 1990, Acosta won the prestigious Prix de Lausanne goldmedal - "If ever there was a day when I was truly happy..." Has he suffered racism in ballet? " Thank God, no," he says. "But dont judge by me. My talent is able to impose itself. People see it and want to help me, not discriminate against me. I went to the English National Ballet as a principal dancer aged 18, and they cast me as the Nutcracker prince, no problem." Then he stops and lowers his voice. "In Italy, when I was asked to dance at La Scala, I did hear directors say they couldnt see me as Romeo." Because of his colour? "What else could it be?"

Immune to false modesty, he determined early on that he would never be typecast. "I refused to be someone who just jumps. I am an artist. I can convey emotion, I can sell a role.

When I joined Covent Garden, I was a principal dancer in my prime ... if people said my look wasnt right, and wanted to give me the part of the jester, Id refuse and not dance at all. After the conditions I grew up in, I wasnt going to come here and be intimidated. All I had to lose was my pride, and I wasnt going to do that.

I endured so much loneliness to cultivate this art, and nobody was going to shatter it." Acosta is cowed by little; he has never been star-struck, never worshipped Nureyev or Baryshnikov - at 18, he had no idea who the latter was. Then again, during his first Christmas in America, he had to ask who the old guy with the white beard was. "I have just slid through life," he shrugs. "I am where I am, but I didnt really mean to be here."

Acosta is passionate - and I dont think its just diplomacy - about broadcasting what Cuba gave a poor boy, how its state-financed training sows the seeds of its own abandonment, schooling dancers so brilliantly that they leave to trade skills for money, second-best export after cigars. When he moved from his short stint as a soloist in the National Ballet of Cuba to Houston, his salary soared from $1 a week to thousands. When invited to join stellar foreign companies, Acosta was granted permission. He didnt need to defect; indeed, he would never have done so, for fear of losing his family. He visits maybe five times a year, local hero and deep-pocketed benefactor.

"In Cuba, talent and money dont go together," he says rather proudly. "The real talent might be in the poorest areas. Billy Elliot is a fantasy, but in Cuba the government provides: money is not an issue in developing artistic talent." And in Cuba, ballet is cool, its competitions never off the television, a rival to football (his first chosen pathto fame) in sparking the dreams of the young.

In his early career, the tough kid found it hard to embody the elegant princes of the classical repertoire, such as Albrecht in Giselle, that he subsequently conquered. "Maybe at first people didnt think I was right for them. Maybe I gestured more like a peasant than a prince. But I have learnt. I love proving people wrong. Its what I do best." The raptures over his recent prince in a Bolshoi Swan Lake seem to prove the point. "Man! The audience were like, 'Wow, a black prince! They had never seen one, but at the end they were all on my side."

Firsts have become a habit: first black principal at Covent Garden, first westerner to dance the Russian classic Spartacus with the Bolshoi in August, a role he loves and cites as a favourite. "In Spartacus, you can project his noble side, or the powerful hero who really wants to win. You dont care about shapes. It doesnt matter how you look - you are going to free everybody."

Acosta could easily have reinvented himself, honed his dress and speech, moved in grander circles, absorbed the ovations and not stressed his impoverished roots. He went though a phase of acting and dressing like a "star" in expensive suits and watches. "But it isnt me. It was just naive." Instead he tells you about being so poor that he was called dirty and smelly at one ballet school; about stealing at another. He is not apologetic, let alone embarrassed. "I was an adolescent, wanting to get noticed by the girls; now I am generous. I build houses in Los Pinos. I do things for the school."

After family, but maybe before dance, the other passion of his life is women. He is now happily settled with a "nondancer", but his serial, tempestuous affairs are described in steamy detail in his book, all names changed. "My editor told me to take out some graphic stuff," he chuckles, like a naughty little boy, "but I really liked it. Its love. Its sex. Its my life."

In 2002 Acosta premiered his autobiographical piece, Tocororo: A Cuban Tale, before a Havana crowd presided over by Fidel Castro (who reportedly talked all the way through). His new creation will open at Sadlers Wells next month: Carlos Acosta with Guest Artists from Ballet Nacional de Cuba, a "not very deep" allegory linking pieces by the Cuban choreographer Alberto Mendez and featuring young dancers from his old school and company.

Is his mission to show the world what his compatriots can do? He laughs. "I end up sounding like the Cuban ambassador, but I try to promote Cuban culture. I want people to be aware of it." For the Royal Ballet, he will reprise his acclaimed warrior Solor in La Bayadère, but it is the home team that excites him.

When the dancing ends in six or seven years time, he will not be chasing ghosts of past glory or trying to mutate into a choreographer. He snorts at the very idea. "Im not a choreographer: Ashton, MacMillan, Diaghilev, they were real choreographers, with 15 masterpieces each."

His real plan is to go home and found his own company, for which the Cuban ministry of culture is already making plans. More important still, he intends to banish rootlessness for ever and reconnect with family in a way that cant be easily severed. "My next project," he says with a cheeky smile, "is to be a father."

- Carlos Acosta with guest artists from Ballet Nacional de Cuba will be performing at Sadler's Wells from 23-28 October. He will also be performing with guests from The Royal Ballet at The Coliseum from 1-6 April 2008.

Comments