In Cuba a documentary prefers them young

- Submitted by: admin

- Arts and Culture

- Caribbean

- Cinema

- culture an traditions

- Destinations

- history

- Society

- 08 / 16 / 2008

Even though it is centered in the person of a girl, the only student in her school, the documentary stops to observe all sorts of things.

The movie was the graduation thesis of Denise Guerra Ribas, a graduate from ISA (in Spanish) in the specialty of photography. It does take its characters out of their usual occupations. It observes them and listens to them from a certain distance. Meanwhile, the camera, revises every detail from the silver face of the countryside, from the tiny work of the insects, from the sedentary existence of house animals, even of the war like life of the fighting roosters.

It could be no les. The slow life of the countryside requires an excess of attention if we want to appreciate it. It demands for a change in the fast moving retina of the person from the city, more used to recognize things from their general characteristics. In the countryside, details acquire another dimension for the sight, they are hidden if they are overseen and they also hide the enigmatic sense of country life.

An insect that goes over a straw, a recently made spiderweb, a foggy dawn are thingts with a heavy weight in this documentary and which demanded a very special performance from the technical team in order to get adjusted to the conditions of the mountain. The story of the documentary, that of the girl and her family, the school and the teacher, would have never been understood without a careful approach to the surroundings in which these people live, an approach that is achieved in Una niña, una escuela with its curious camera.

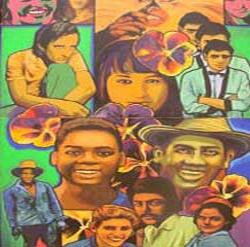

Even though Él, ustedes, nosotros is structured on interviews, its dynamism, its surprising movement, is achieved thanks to the fact that it seems as if it wanted to avoid the people being interviewed, as if it wanted to put them aside, in order to concentrate on the painting by Raúl Martínez. Because it would have not been enough with the tour it makes around his work in order to reach him, if they had not had their own desire to appear. In fact, in the documentary, the paintings by Raúl come crawling behind the people being interviewed, sometimes gently, but sometimes like beasts lying in wait, as if waiting for the opportunity to jump on them and overcome them.

It may have been impossible to offer a better idea of this man in the biography than insinuating this subversive attitude of his pieces in order to making him seen.

That is at least inferred from the words of the guests. Warily, sincere, neurotic, generous, obsessive, tender, these are all adjectives that fight each other in order to define this complicated man. Affectionate, sometimes; sometimes unpleasant, Raúl seems to have earned the respect of his friends through his kindness. People being interviewed seem to dream when they remember him.

Divided into three parts, the documentary has two main moments: the work of Raúl Martínez and his life, that even though they are separated, they both show their coincidences everywhere. Léster Hamlet started from an idea by Abelardo Estorino, he gave it a very particular dynamic to the narration and created a character filled with nuances.

An enemy of rhetoric, a friend of looking twisted into the great truths, sometimes alienated, loudly praised, Raúl lived between two opposite worlds, between abstraction and imagination. First he was abstract, he followed an inside search; afterwards he was imaginative, he allowed himself to be impressed by all sorts of external stimulus. Out of this mixture, he achieved an iconography that was a daughter to North American pop, but with a very personal characteristic.

But there are many other antagonisms to be seen in the documentary. Raúl Martínez draw multitudes without considering himself to be a great communicator. According to him, he would have been happy to have a single admirer believing in his painting. He was an enemy of fashions, but his art had always something of informational currency. He was open to the unknown, even though he used to resist it. Apologetic and ironic, he criticized and celebrated at the same time whatever he found in his way.

(Cubacine)

Comments