Cuba’s food ration stores mark 50th anniversary

- Submitted by: lena campos

- Politics and Government

- 07 / 13 / 2013

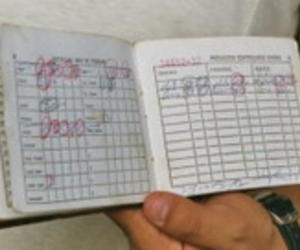

The Cuban government calls it a “supplies booklet.” Cubans call it a “rations booklet” or simply “la libreta.”

Either way, half a century after its creation, the booklet has come to symbolize the epic failure of Cuba’s agricultural sector and the communist government’s stubborn insistence on an egalitarian subsidy for each and every one of its 11 million people.

The hundreds of state-run food stores that distribute the rations are marking their 50th anniversary Friday, although the decree creating the system was issued in March 1962, at a time when U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba were beginning to cause shortages of food, medicines and other supplies.

Cuban ruler Raúl Castro two years ago called for an “orderly” end to a system “under which two generations of citizens have lived, this rationing system that despite its toxic egalitarian character offered all citizens access to basic food at laughable prices.”

Castro has been pushing a series of market-oriented reforms to drag his economy out of the doldrums, cutting back on subsidies and other public spending, slashing state payrolls and allowing more private enterprise.

The booklet in fact has been shrinking over the decades, and especially after the early 1990s, when Cuba lost its $4-$6 billion a year subsidies from the Soviet Union and had to tighten its belt to the last notch.

Today, the government spends an estimated $1 billion annually on the system — unique in the world for its level of detail and coverage — a huge number in a nation where the average official salary stands at less than $20 per month.

With an agricultural sector all but stagnant after a half-century of central government controls, Cuba must now import up to 80 percent of the food it consumes, fueling an import bill estimated at more than $1.5 billion per year.

Cubans pay less than $2 for the items they receive under the ration card — an estimated 12 percent of real value — a lifesaver for the poorest of the island’s poor and a help to every man, woman and child regardless of their income.

Yet, the food rations last only about 10 days out of every month. For the rest of the time, Cubans must buy in markets where much higher prices are set by the laws of supply and demand.

Each Cuban is now supposed to receive a monthly ration of seven pounds of rice, half a bottle of cooking oil, one sandwich-sized piece of bread per day plus small quantities of eggs, beans, chicken or fish, spaghetti, white and brown sugar and cooking gas.

Children get one liter of milk and some yogurt, diabetics get special booklets for their diets and there are special rations for special occasions — cakes for birthdays, rum and beer for weddings, uniforms, pencils and notebooks for the start of the school year.

But not all those rations are always available each month, and the number of items and the size of the rations have been dropping for years. Gone are potatoes, soap and tooth paste, salt, cigarettes and cigars and liquid detergent, among other items.

Today the booklet, printed on cheap paper that turns brown, is issued to each of Cuba’s 3.6 million families and has 20 pages, compared to 28 pages in earlier years.

And while the rations account for only a small part of their consumption, Cubans say they fear that the total removal of the system will deliver a harsh blow to retirees whose fixed incomes average $12-$14 per month.

One Cuban axiom holds that “No one can live on the booklet, but there are a lot of people who can’t live without the booklet.”

There has been talk in Havana of replacing the booklet of poor people with something like food stamps, but Castro has made it clear that he wants to eliminate the entire rationing system.

Rationing was introduced “with an egalitarian intent in a time of shortages,” he declared in 2011. But with the passing of time, it has turned into “an unbearable burden for the economy and a disincentive to work.”

Source: Miami Herald.com

Comments