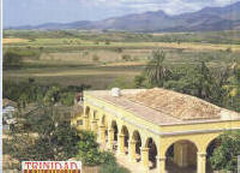

Sugar Mill Valley in Trinidad, Cuba

- Submitted by: admin

- Local

- Travel and Tourism

- Arts and Culture

- culture an traditions

- Destinations

- Sancti Spiritus

- Society

- 04 / 13 / 2009

When Don Alejo Maria del Carmen Iznaga y Borrell ordered to build a luxurious 43.5 meter high brick tower on his estate –which still seduces visitors- he was surely far from imagining that almost two centuries later, from the top of its dome, not a single sugar cane field would be seen in the entire region.

Don Alejo had his tower built of a solid structure distributed on seven levels, with geometric shapes ranging from square to octagon, with prolonged arches and an interior staircase up to the top. This has led experts to suspect that beyond the myth and the utilitarian purposes attributed to it as a surveillance system, the real origin of the project had to do more with the pleasure of ostentation and vocation for aesthetics than to the merely pragmatic.

The tower, impassive and loved by just about everybody, has changed little or almost nothing in its 200 years of existence, whereas the landscape is not the same that Don Julio German Cantero described in mid 19th century in his Libro de los Ingenios (Book of the Sugar Mills), illustrated with care and a lot of patience by French engraver Eduardo Laplante.

"The lands of the Manaca sugar mill —pointed out Cantero, one of the most prominent representatives of Trinidad’s sugar rich at the time— are famous for being the best of the entire valley. Most of them are red, and in some sugar cane grows to an incredible height."

Located to the north and east of Trinidad and south of the Escambray Mountains, the Valle de los Ingenios, designated by UNESCO as a World Cultural Heritage Site since 1988 along with Trinidad’s historical area, constitutes a sort of triangular plain covering some 250 square kilometers and that includes the San Luis, Agabama-Meyer and Santa Rosa valleys, besides the coastal plain of the south, delta of the Manatí River.

Roberto Lopez, who was a profound expert of the region and who until his premature death was the head of the City Conservator’s Office for Trinidad and the Valle de los Ingenios, wrote that in the area," nature, with its infinite fertility allowed man to create a culture of plantation, a sugar empire, maintained on an inhumane base of slavery and poverty, but capable, in its paradoxical wonder, of synthesizing a history of splendor and decadence, of work and wealth, of foundations and relations with the outside world."

Suffice is to know, for example, that in 1827 during the so-called economic boom, there were 56 sugar mills in operation in the territory, with the surprising figure of 11,700 slaves, which all together contributed a production of almost 640,000 arrobas (one arroba equal to 25 pounds) of sugar, incomparable at the time with any other part of the world, a development that would continue until mid 19th century, when the crisis occurred and therefore the region’s decline and the end of Trinidad’s prosperity.

Manaca-Iznaga, Guáimaro, Buena Vista, San Isidro de los Destiladeros: A total of 73 archeological sites, including 13 estate houses, some of them with their towers, boilers, industrial systems of the time and remainders of sugar production, have survived the passage of time and escaped almost miraculously from twisters, storms, telluric movements here and there, hurricanes, and of course the voracity of the elements, and what’s even worse, the action of human beings themselves.

However, in spite of good intentions, not all have had the fate of Manaca-Iznaga, the main building of which, recovered decades ago and turned into a restaurant and commercial establishment attached to the Tourism Ministry, is today an emblematic place of the entire Valle de los Ingenios.

From the tower guarding them, where tens of thousands of tourists arrive every year, the main contrasts of the Valley’s landscape can be perfectly evident. Among them is the proliferation over the last few years of houses with zinc roofing, which, as impertinent mirrors, are obviously out of place, in an environment where clay tiles imposed their class several centuries ago.

It’s worth clarifying that zinc never got to Manaca-Iznaga and other areas of the Valley do to anybody’s whim, but as an alternative in view of the loss of roofing after the passage of the latest hurricanes, a situation that is permanently monitored by the authorities, in this case by the Curator’s Office, which has entrusted the Municipal Housing Department with the replacing of this material with clay tiles, an action that has not become a reality due to lack of materials and financing.

Such reality doesn’t make sense if we take into account the tradition of Trinidad’s ceramics and particularly the proliferation of tile factories in the Valley, most of them currently in a sorry state of neglect. The Curator’s Office plans to recover some of these factories, that in the future could supply materials to the region and at the same time join the Valley’s tourist attractions.

As if the question was burning him, Livan Cantero, an adolescent that only inherited his surname from that caste, fits his cap up to his ears and launches his truth:

—It’s that the Valley without sugar cane is not the Valley, It’s as if it had been transplanted.

A consequence of the process of resizing Cuba’s sugar industry, the closing at the beginning of this century of the CAI FNTA, the former Trinidad sugar mill, not only represented the disappearance of the last heir of Trinidad’s sugar mills, but also –and perhaps the most worrying aspect- the rapid disappearance of sugar cane and the resulting growth of marabou and other undesirable plants, which represented a dangerous imbalance in the area’s landscape.

Knowing what this forced mutation represented for the area, authorities in the territory, with the consent of the ministries of Sugar and Tourism, the participation of the National Enterprise of Flora and Fauna, and the Curator’s Office, have made an effort to restore the environment in two directions: to reduce the 2,000 hectares of marabou growing on the plain in March 2008 and to recover sugar cane cultivation, a required referent at the Valle de los Ingenios.

Thus, stretches of land planted with sugar cane and king grass are increasingly making those areas of greater visual impact green again, which translate into a guarantee for animal food, since, as warned by Victor Echanagusia, a specialist with the Curator’s Office. "it’s not a matter of creating a set design either, a facade to satisfy the interests of tourism, but of making every recovery attempt contribute social benefits."

Perhaps this is the best formula to preserve a region where at the end of the 18th century and early 19th century the fortune of opulent Trinidad was created, and where today a mystic is growing that’s perhaps more captivating than all the fortune that preceded it.

Comments